Crafting a narrative is seldom devoid of challenges and hardships. One’s voice must exude confidence and excitement, while retaining the authenticity of the character. And crucially, the voice is responsible for shaping a story that can transgress conventional boundaries, particularly those prevalent in eighteenth century society, both in Britain and beyond. Helen Maria Williams and Mary Prince, the two authors I will be focusing on, were both women who defied social expectations by using their voice to recount or construct a narrative. Prince, a slave from Bermuda, became the first black woman to publish an autobiography in Britain, all while still being legally enslaved. Williams defined gender norms by directly engaging with the French Revolution, despite the social resistance to her political takes on the matter.

This essay will argue that, through their accounts, The History of Mary Prince and Letters on the French Revolution redefine female power as an act of survival, rooted in testimony, defiance, and the ability to shape narrative, paralleling Cosway’s depiction of subdued yet radiant female strength.

When addressing the matter of female power, we must remain acutely aware of the two opposing forces that define the conversation, those being oppression, and conversely empowerment. Neither can function without the other, and both novels utilise the tension created to emphasise their contents, whether that be directed at the French Revolution, or the horrors of slavery. However, the primary mechanism by which this effect is achieved, is none other than personal narrative. Literary form is crucial in shaping the flow and overall reception of a text, altering how the reader views its contents, where a personal form can present itself as much more intimate and sincere, completely changing how the narrative functions. Williams writes her letters in the form of a first-person account, asserting herself as an ‘eyewitness historian’. She follows the events of the French Revolution closely, reporting on all major incidents as they happen, from the Fall of Bastille to the Reign of Terror. It’s important to state that the letters are addressed to an unnamed, fictional friend. Williams could have chosen any form, but instead went for the fictional letter, suggesting a deliberate choice on her part – but to what effect? In her study on form, An “Englishwoman’s Private Theatrical”: Helen Maria Williams and the New Female Citizen, Weng posits that Williams primarily ‘deploys the epistolary form to justify her interest and enthusiasm for the Revolution’ (348). This much is true. Williams’ excitement for the revolution is a topic much spoken about by critics in the nineteenth century. In Letter III, she outright states, “I too… rejoiced in their happiness, and repeated with all my heart and soul, “Vive la Nation” (Letters on the French Revolution. 16). However, Williams knowingly outlines her support for the French Revolution in spite of the largely negative attitudes of people back home. Her writing was a direct response to Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, which had just been published. As such, Williams’ power and authority lies not only in the fact that she crafts her own account of the narrative, but also directly challenges male political figures as a female writer. To sum it up, ‘the unassuming genre of the familiar letter blurs Williams’ identification between her position as a woman and her position as a writer’ (Robinson. 11). It grants her the authority to comment on serious political matters and the ability to influence people back home.

The History of Mary Prince achieves a similar effect, blending voice and form to reconstruct a narrative that has previously been told for her by others. This autobiographical text depicts the brutal realities of slavery, the many stories which forever go untold and remain hidden. Empowerment and liberation in the text are achieved through narrative voice. In her study on resistance in The History of Mary Prince, Baumgartner states that ‘Prince makes meaning and sense out of her suffering through the telling of her story, rereading the residual marks of slavery left on her body and inscribing a new and different text’ (253). The very act of writing is an act of defiance, yet this time the story belongs to her, and form is what enables the reader to feel and connect with her suffering on a deeper level. Hypothetically speaking, Prince could have retold her story as a fictional tale, about a fictional character undergoing the struggles of slavery. Yet, she didn’t. I’d further argue that her physical account of the story through her autobiography is symbolic of the physical scars left on her body. The text and her suffering are highly interlinked, and taking control of the narrative is Prince’s way of taking control of her own trauma and suffering. This first-person account magnifies the inhumanity of slavery and empowers Prince as a former slave, but also a woman. The story becomes hers.

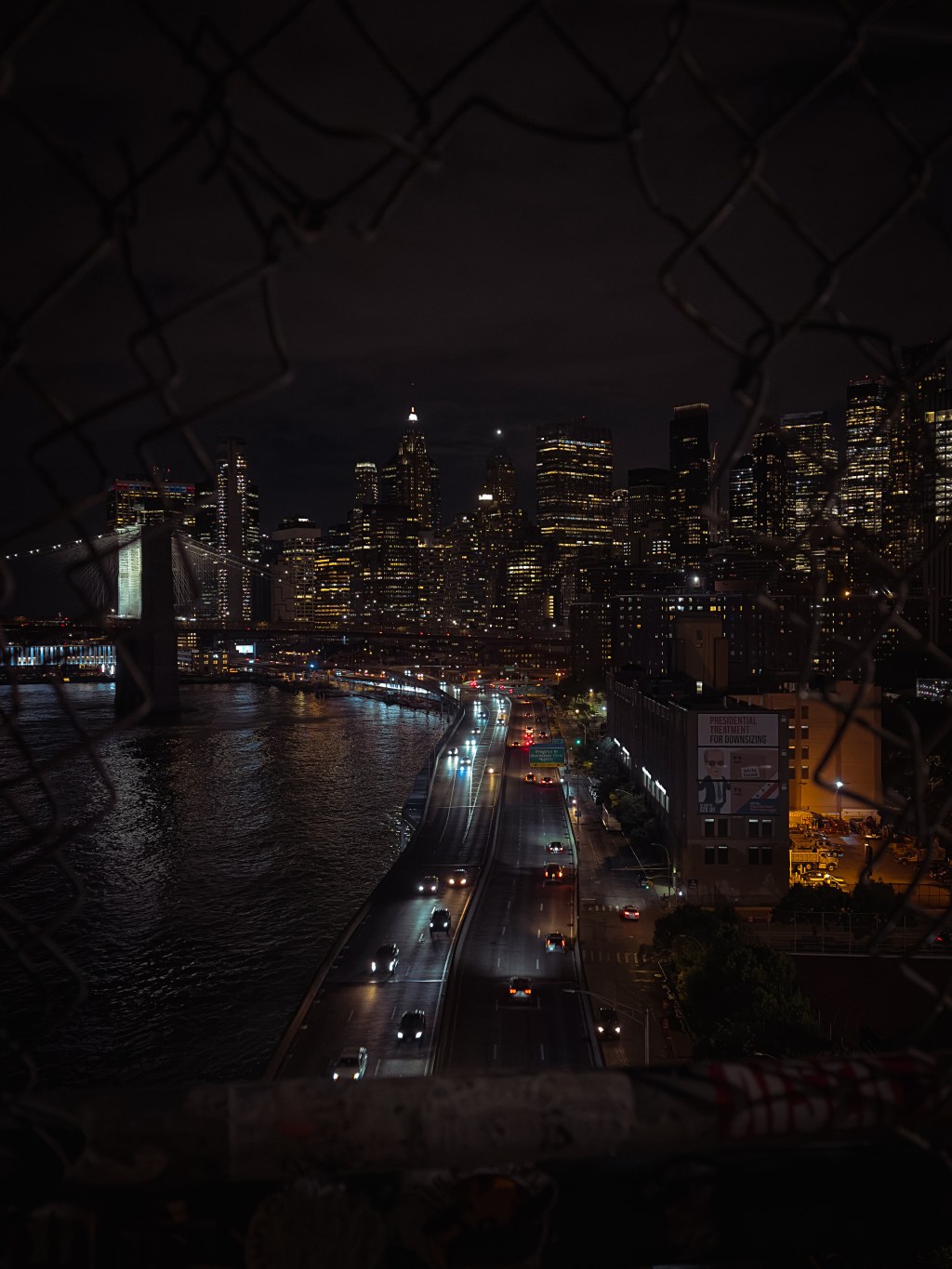

Claiming ownership of the narrative was crucial in disrupting the male driven cultural scene, not only in literature, but across all the arts. In 1782, Cosway painted ‘Georgina as Cynthia’, an image of the 5th Duchess of Devon walking out of the dark night. Georgina is placed directly in the centre, with her hands pushing herself forward away from the clouds. I’d argue that Georgina is being depicted as in control of the narrative. Her movement is deliberate, not an accident. The contrast between the dark background and her bright figure only further promotes Georgina’s authority. Cosway herself was an admirable and powerful woman, being highly politically active. From her friendship with Thomas Jefferson, to her liberal attitudes, Cosway took ownership of her own life in all possible ways. This striking painting thus shares much in common with the two texts I spoke about. The notion of ‘power’ is not inherent or innate but must instead be sought after and claimed by redefining the narrative itself.

However, the narrative is simply the mechanism by which power is achieved. It is a tool, but without the adequate subject, the tool has nothing to work upon. In this case, female power is directly achieved by defying social and gender roles, with narrative simply acting as the platform by which both authors can showcase female characters defying social expectations. In Williams’ Letters on the French Revolution, this is primarily executed through the writing itself. She engages with heavily politicised matters, keeping her perspective on the revolution broad enough for stories of all kinds to seep through, stepping away from the male-centricity that politics tended to invite in literature. In fact, a pattern was emerging – that being ‘an increasing amount of women engaging in public affairs and involved in shaping the political culture of this period’, to which Williams was simply responding (Weng. 348). A perfect example of this is Letter IV, where Williams reflects upon the chaos taking place on the day the Bastille fell. She writes, ‘The women too, far from indulging the fears incident to our feeble sex, ventured to bring victuals to their sons and husbands’ (20). This is in stark difference to, say, Burke’s writing on the revolution, which was less diverse in perspectives. Ultimately, In her recounting of the revolution ‘Williams blurs the distinction between observer and participant, English and French, the monarchy and the people, and individuals’ faces with those of the masses (Robinson. 10). Prince’s writing goes a step further, transgressing boundaries on the basis of gender, as well as race and identity. Steven Cason, a scholar specialising in literary historical narratives, argues that ‘as a black woman, Prince faced the estrangement of neither belonging in the same social group as white women, nor that of a black man’ (2). Indeed, Prince defied expectations from multiple angles. Critical Race Theorists of the 80’s point towards the impact of economic, social, and linguistic inequality segregating communities and ethnicities, relating it back to historical motives. Prince’s autobiography starts, ‘I was born at Brackish-Pond, in Bermuda, on a farm belonging to Mr. Charles Myners’ (1). From the onset, Prince is afforded neither economic, nor social freedom. In fact, she is by birth the property of another man. Her autobiography had to be narrated, as Prince herself was not given a formal education. This further strengthens my argument, showcasing Prince’s ability to defy expectations from multiple perspectives.

Her ability to do so parallels Cosway’s ‘Georgina as Cynthia’. Particularly, Georgina herself, who was a devoted Whig. Her life was complex and bold. She climbed Mt. Vesuvius in 1787, was known to be politically active, and was generally known for her extravagance. This is reflected in the painting, from the crescent shaped headdress to her diaphanous clothing. She fully embodies Cynthia, the Goddess of the moon. Her depiction is strikingly powerful, and her figure stands alone, without being in the male gaze.

Lastly, I’d like to look into power through emotional and ethical influence. This ties into my previous point, as I believe that the way the narrative is structured, creates a dynamic through which Prince’s and Williams’ accounts are highly emotive and sentimental. The language used throughout only aids in getting the readers to emphasise with the two authors, further solidifying their authority. When describing her ‘love of the revolution’, Williams calls it ‘entirely an affair of the heart’ (43). Her depiction of the events are always written through a personal lens, rather than being objective. Her use of language excites and evokes, rather than simply describing. LeBlanc argues that ‘Williams’ sentimentalism draws on eighteenth century culture of feminine sensibility’ (26). While this stylistic choice was made to improve her chances of selling back home, her decision to draw on sentimentalism cannot be neglected. Prince too makes use of emotive language to garner credibility, sympathy, and authority as a writer. Her writing mimics the nature of her suffering, ‘Oh the horrors of slavery’ (11). The use of raw sounds and harsh consonants is evident and audible. Moreover, a constant repetition of ‘God’ is made throughout the text. Prince draws on religious feelings to intensify the empathy her writing garners.

An emotional connection is harder to point to in Cosway’s painting, however I’d argue that notions are hinted at through its composition. Despite her God-like nature and beauty, Georgina stands in the painting all alone. Perhaps an attempt is made to get us to sympathise with that. By nature, the painting will be looked at and enjoyed for a while, until it will no longer be admired. The novelty will wear off, and Georgina will once again be forgotten.

Since the time of their publications, many critics and scholars have attempted to explore any and all aspects of these texts, yet the feminine aspect has often been overlooked. Prince’s writing is often explored in the context of racial division, and Williams’ is judged for its lack of ‘reason’ and ‘logic’, critiqued for being too sentimental. In this essay, I aimed to centre the discussion around elements of female strength and authority, exploring how structural narrative and form enable them to transgress social boundaries surrounding who should write and what should be written. Prince and Williams are the perfect example of how expectations should be broken in literature. When coupled with Cosway’s ‘Georgina as Cynthia’, this essay achieves a balanced and thorough examination into how female power is achieved in the texts.

Works Cited

Baumgartner, Barbara. “The Body as Evidence: Resistance, Collaboration, and Appropriation in ‘The History of Mary Prince.’” Callaloo, vol. 24, no. 1, 2001, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3300499

Burke, Edmond. Reflections on the Revolution in France. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Cason, Steven. “The Pluralised “I”: White Appropriation of Black Women’s Voices in The History of Mary Prince: A West Indian Slave Narrative”. TCNJ Journal of Student Scholarship, volume XXIII, 2021.

Cosway, Maria. “Georgina as Cynthia”, 1782.

LeBlanc, Jacqueline. “Politics and Commercial Sensibility in Helen Maria Williams’ Letters From France.” Eighteenth-Century Life, vol. 21 no. 1, 1997. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/10402.

Prince, Mary. The History of Mary Prince A West Indian Slave. Gutenberg, 2006. https://gutenberg.org/files/17851/17851-h/17851-h.htm

Robinson, Laura M. “The Face of Hope: Helen Maria Williams and the Revolutionary Countenance”. NC State University Libraries, 2008.

Weng, Yi C. “An “Englishwoman’s Private Theatrical”: Helen Maria Williams and the New Female Citizen”. Institute of European and American Studies, vol. 49, no. 3, 2019.

Williams, Helen M. Letters on the French Revolution, Written in France, in the Summer of 1790. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/N18502.0001.001